A few days ago, I bought my first pair of reading glasses.

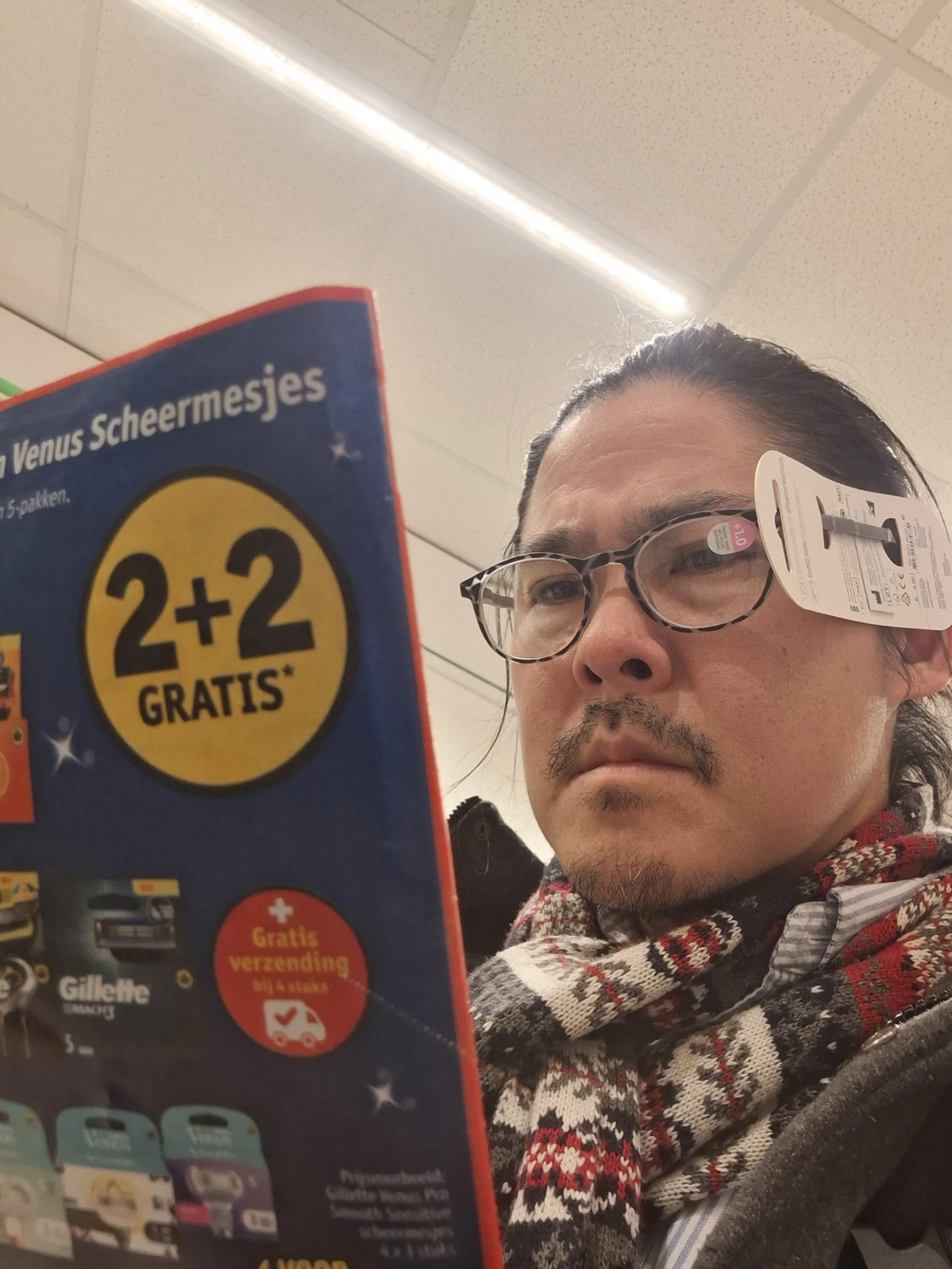

For the last few weeks or so, I had been under a bit of stress and (perhaps as a result), I had some trouble reading texts on my phone or the stack of papers I had to grade. After a few days of trying to muster the courage to try on a pair of reading glasses, I finally managed to go to the shop to try on a few.

To my horror and dismay, the reading glasses helped me read the otherwise blurry letters on my phone. So I hesitantly purchased the least offensive pair I could find.

I felt reluctant putting them on, but I also couldn't deny the reality that it made things easier to read. For several days, I tried getting used to the idea that I no longer was the young lad that I still imagined myself to be and I was beginning to cope with this unwelcomed reality.

Earlier today (the first day of my so-called holiday with my family visiting the inlaws up North), I made a shocking discovery while putting on my contact lens. Turns out, for about a week+, I had my right lens (the one with astigmatism) in my left eye and my left lens (the one without astigmatism) in my right eye.

I switched them around and I was able to read clearly, without my new reading glasses.

So apparently, I'm still not that old, but I'm a lot dumber than I thought I was, which is a different sort of problem all together.

In any case, Happy Holidays everyone (and if anyone needs an extra pair of +1.0 reading glasses, I have a spare) 🤪