“No is the single most powerful word in the English language, [but…] it's a very tough weapon to deploy. Everyone knows how difficult it is to say no. It's one of the reasons why people seem to be comfortable asking you for favors they have no business asking you for. They know how hard it is to say no.”

Shonda Rhimes in “The Year of Yes”

Tomorrow, I’m running a workshop on “Saying No in Academia'' for the Dutch Sectorplan on Transformative Effects of Globalisation in Law at its annual networking event. The irony of it all is that I’m not very good at saying no (hello imposter syndrome). I actually failed at saying no to doing this event. Part of the reason why I suck at this is because I (used to?) equate being a good person with being a person who did not say no to people asking for help. I’ve always been a people-pleaser and an external-validation addict, which I (very recently) learned are serious character flaws.

Rousseau once compared being polite to being inauthentic (and thus deceitful). He elaborated that being polite - for example, by saying yes to something you don’t actually want to do - is to compromise on what you really want and to sell your true self short. While I’m not advocating for impoliteness, I do believe that being true to your authentic self and being able to say no are important skills that are seldom taught in classrooms (especially in the Japanese classrooms that I had to sit through).

The wonderful Brazilian novelist, Paulo Coelho, elegantly summarized this point as follows: “When you say yes to others, make sure you are not saying no to yourself.” For the longest time, I was not following Coelho’s advice. I had been mindlessly saying yes to others for so long that at the ripe old age of 40, I still cannot clearly define what it is that I want for myself. There is no shortage of self-help books and “literature” claiming that they can help one become better at saying no, but I find that most of them often tend to be rather superficial. For what it’s worth, I combed over a bunch of them just so that you don’t have to (hello people-pleaser) and the collective summary of the literature goes something like this:

Form a “NO committee” with a group of friends or colleagues that encourage you to say no. Check in with them regularly to share stories of how you turned down something or how they said no to an undesirable task. Bonus points if you can find a group member or an ally more senior than you (or who have more experiences), as they may serve as your saying-no-role-models.

Keep track of what you say yes and no to and reflect on it from time to time.

Rethink your priorities. Saying yes to something inevitably means you are saying no to something else. Make sure what you are saying yes to is in alignment, not only with your priorities, but your values. Also, stop comparing yourself to others as they may have different priorities, values, and goals. As the “wisdom” of Instagram suggests, a flower does not compare itself to other flowers, it simply blooms. So go on and just bloom!

Don’t answer a request right away (unless you can give an immediate no). If you must, deflect with a “let me think about it and get back to you,” and really think about whether it is something you want to do. If they don’t get back to you, you don’t even have to bother saying no.

Saying no may stir feelings of guilt or shame within, and some of us may try to avoid these negative feelings by reluctantly saying yes to something they ought to have declined. What can alleviate these negative feelings is to explain to the favor-seeker, why it’s a no for you (e.g. “I’m sorry but I am super busy with another task” or “I would love to, but I’m in Mars on that day and won’t be on Earth.”). It will help them understand why you cannot. This may diminish some feelings of guilt and shame (as it solicits their empathetic understanding), and in doing so, it may also preserve your relationship with the requestor as you have a good reason for rejecting them.

Offering a “strategic no” may help create an “illusion of scarcity” around you (e.g. “This person is so busy and in such high demand, they must be really good!”).

Remind yourself that saying yes can actually be physically and psychologically harmful: “A propensity to say yes to everything can lead to burnout, mental and physical health problems…”

Learn to appreciate the joy of missing out (JOMO).

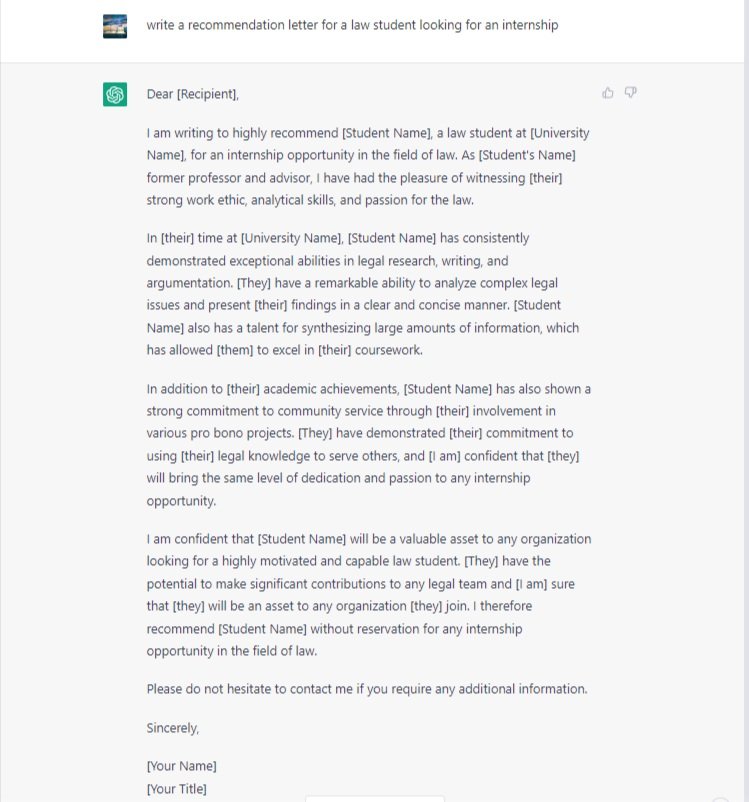

All of these tips may help us in some situations, but it may not help - for example - a young academic trying to assess which engagements they can say no to (and get away with) and which tasks they must say yes to (or risk career-suicide). It’s tough out there for young academics just starting up because bosses, supervisors, colleagues, and students will all want something from them (e.g. “Can you teach this course?”, “Can you peer-review this?”, “Can you write me a recommendation letter?”, “Can you be on this taskforce/committee?”, “Can you be my thesis advisor?”, “Do you want to write an article and apply for this grant with me?”, etc.). And as the Shonda Rhimes quote at the top suggests, some people will ask for all sorts of things (that they know they shouldn't be asking), because they know how hard saying no is (especially to a boss). They know that we all want to be a good person and a team player and some people will try to exploit that to your detriment.

As a side note, the Maastricht Young Academy recently hosted a Growing Up in Science event with the Rector of our University - Pamela Habibović - who noted that for young researchers just starting up, it may be particularly difficult for them to say no (and perhaps they should not), because saying yes will indeed expand their networks and stimulate new trails of thought that may contribute to their research. So we shouldn’t always be saying no, but we just have to get better at saying no to certain things, which brings us to the next point.

For most academics, young or old, we want to strive towards becoming the go-to person in that field or some niche therein. To combine one of the popular tips suggested in the bullet point and the wisdom of our Rector, we should develop a better sense of who we are (i.e. our authentic self), what we want to accomplish, and what makes us happy and use these criteria to determine more thoughtfully what we say yes and no to. We can ask questions such as: “Is this part of my research line?”, “Will saying yes de-stabilize my personal life?”, “Who am I doing this for?”, and so forth. Whether you actually do this everytime you are confronted with a task or a favor, ultimately comes down to your personal incentives and what drives you to want to say no.

For me, two factors motivate me to want to say no more: 1) Having kids realigned my priorities, and 2) the disappointing realization that having said yes to too many things, the quality of everything I was doing - from research to teaching and being a good father/partner - all suffered a noticeable decline. It still hurts me to admit this, but it is true. So by saying yes, not only did I lose my authentic self in the process, but I was becoming mediocre at everything I was doing. One of my colleagues who I shared this thought with recently responded that he knew exactly what I was going through as he felt the same way: everything he was doing could have been better if only he had more time. How we make time, and to shed this very negative, nagging feeling that we are not good enough, starts with one word: no.

In the end, saying no is a mechanism of protection and an act of self-compassion. I do not want to feel like I am mediocre at everything anymore. Instead, I want to be good at the things I selectively choose to care about. This will inevitably mean that I will miss out on certain things (bye promotion?), but it won’t bother me as much because I made deliberate choices in the interest of my authentic self. Brian Little and Adam Grant’s work note that one’s well-being is intricately tied to the sustainable pursuit of core projects, which are passionate commiments that align with our values. Saying no buys us time for these pursuits. Now say it all with me. NO!